Autistic Hacker Helped FBI Nail Anonymous Boss

Charge dropped after man, 26, cooperated

View Document

Madden Sealing Order

-

Madden Sealing Order

-

Madden Sealing Order

-

Madden Sealing Order

-

Madden Sealing Order

-

Madden Sealing Order

Madden Complaint

-

Madden Complaint

-

Madden Complaint

-

Madden Complaint

-

Madden Complaint

-

Madden Complaint

-

Madden Complaint

-

Madden Complaint

-

Madden Complaint

-

Madden Complaint

Search Warrant #2

-

Search Warrant #2

-

Search Warrant #2

-

Search Warrant #2

-

Search Warrant #2

-

Search Warrant #2

MAY 13--In an effort to identify leaders of Anonymous, the FBI arrested an autistic New York man and then used him as a cooperating witness to help snare a notorious fellow hacker who was subsequently indicted for his central role in a series of high-profile online attacks, The Smoking Gun has learned.

MAY 13--In an effort to identify leaders of Anonymous, the FBI arrested an autistic New York man and then used him as a cooperating witness to help snare a notorious fellow hacker who was subsequently indicted for his central role in a series of high-profile online attacks, The Smoking Gun has learned.

In return for the hacker’s cooperation--and in light of his autism--Department of Justice officials initially agreed to defer prosecution on a criminal complaint charging the man with hacking Gawker Media, an illegal incursion that yielded registration information for more than a million individuals who signed up with the popular blog network.

Federal prosecutors eventually dropped the hacking charge altogether, according to court records that were kept under seal long after the hacker’s arrest by a team of FBI agents. Investigators were concerned that if the man’s cooperation became public, he would be harassed by hackers then being targeted by the FBI. Additionally, disclosure of his cooperation, prosecutors contended, “would jeopardize  substantial ongoing investigations into the defendant’s former co-conspirators, many of whom are suspected of carrying out substantial computer hacks against several businesses.”

substantial ongoing investigations into the defendant’s former co-conspirators, many of whom are suspected of carrying out substantial computer hacks against several businesses.”

So, to “help ensure the defendant’s safety,” Thomas “Eekdacat” Madden became, for a time, “John Doe.”

The 26-year-old Madden, whose cooperation has not been previously disclosed, lives with his parents in Troy, a city 10 minutes outside Albany. An only child, Madden graduated in December 2010 from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, where he completed a double major in computer science and mathematics, according to school records.

Madden grew up in New Jersey, but moved with his family to upstate New York months before beginning his studies at RPI, which is regarded as one of the country’s premier engineering and technological research universities. The Madden family’s relocation to Troy--where RPI’s campus is located--was prompted by Thomas’s need for support during college. In an interview, Kenneth Madden told of driving his son to class, adding that while Thomas was “high-functioning,” he was “severely autistic” and could not live on his own at the university.

Madden said that his son’s autism diagnosis “goes back to nursery school” and that Thomas has struggled with “sound issues, loud noise, the eye contact.” While acknowledging his son’s brilliance with computers and math, Madden referred to “both ends of the spectrum,” saying that his son’s condition is “a gift and a tragedy and a blessing.” He added, “If you ever saw the movie ‘Rainman,’ it’s like that.”

During a recent phone conversation, Thomas Madden declined to speak about computer hacking, saying that he has had “no contact with those people” since his arrest. In halting speech, he politely refused to address other topics, noting that a reporter’s questions were  “getting into extra-legal territory.” Though he previously told FBI agents about his affiliation with certain hacking groups, Madden denied such connections to TSG. When asked if prosecutors had mischaracterized him in court filings, Madden replied, “Evidently.”

“getting into extra-legal territory.” Though he previously told FBI agents about his affiliation with certain hacking groups, Madden denied such connections to TSG. When asked if prosecutors had mischaracterized him in court filings, Madden replied, “Evidently.”

The government’s efforts to shroud Madden’s identity--as well as his cooperation--were an unqualified success. Madden’s name does not appear in the blizzard of stories about criminal probes into the members of Anonymous and its various splinter groups like Internet Feds or Lulzsec.

In fact, Gawker itself seems unaware that the FBI actually arrested someone in connection with the theft of its source code, databases, and confidential records. That online incursion--reportedly prompted by Gawker’s “arrogance”--was a publicity coup for Madden and his cohorts. “over 1 million people got compromised because of me,” he boasted during a chat with an online acquaintance. He later crowed, “I feel a bit better today cause I got the attention of the entire western world lol.”

Other chat transcripts show Madden referring to a stolen file containing the grades of thousands of students. While he was only seeking the records of three specific pupils, he noted, “this warrants the theft of 11,000.” He also wrote that he did not deface sites he had breached. Instead, he preferred to maintain discreet access to the compromised destinations so he could “farm them for weeks.”

News reports make it appear that the sole informant used by the FBI to help target top hacking groups was Hector Monsegur, 30, who was “flipped” by agents following his arrest in early-June 2011. Monsegur, a veteran and wily hacker, is scheduled to be sentenced later this month on a variety of federal felony charges. Known as “Sabu,” Monsegur is reviled online, where so-called hacktivists have savaged him as a manipulative traitor who, when caught, sought comfort in the FBI’s arms.

While Madden was busted three weeks after Monsegur (seen below) began cooperating with federal investigators, his June 2011 collar was not connected to the older hacker’s work with FBI agents. Chat transcripts, interviews, and court records--some of which remain under  judicial seal--offer a detailed account of how Madden was snared by FBI agents following a falling-out with an online acquaintance.

judicial seal--offer a detailed account of how Madden was snared by FBI agents following a falling-out with an online acquaintance.

Madden got his degree from RPI in December 2010, the same month that Gawker was victimized by Gnosis, a hacking group that congregated in a private online chat room. During debriefings following his arrest, Madden told FBI agents that he was a member of Gnosis and other online groups, including Patriotic Nigras, a band of “griefers” who caused havoc on Second Life, the online virtual world.

He eventually graduated to computer intrusions involving the theft of large amounts of data, unauthorized accesses that were aided by password cracking and network security scanner programs. During a chat months before the Gawker hack, Madden declared, “we run one of the largest data mining operations on the net just with passwords, google of hacking.”

As detailed in the criminal complaint filed against him, Madden chatted openly about his illegal online exploits with an acquaintance with whom he had exchanged messages for several years. Madden, according to the FBI, copped to the Gawker hack “as well as other unauthorized intrusions of protected computer networks” during chats with the acquaintance, whom agents described as a “college student in New York.”

Madden told his online friend about Gawker’s weak security, remarking that the blog network’s “encryption was over 10 years old I forget their OS was like 9 updates behind big updates.” As for his accomplices, Madden said that “someone big” was involved, but that, “I don’t know any of these people beyond their handles and countries.” Referring to a Gnosis statement taking credit for the Gawker hack, Madden wrote, “haha I wrote that line the other day.”

The collegian with whom Madden corresponded apparently was a young woman, according to Kenneth Madden, who added that his son helped the student “with mathematics and then ended up getting fooled into doing the homework for the person. And tests and online ![]() things like that.” Madden remarked that his son “can be fooled or tricked easily.”

things like that.” Madden remarked that his son “can be fooled or tricked easily.”

At some point, however, Madden realized he had been duped by the other student. So he opened a Yahoo account in a fake name and sent an e-mail to one of the other student’s teachers. “He let the person’s professor know that that person was cheating,” recalled Kenneth Madden.

Though he had shared details of his own criminality with the other student, Madden apparently did not foresee the possible repercussions of accusing the acquaintance of being an academic cheat.

The blowback came in the form of a criminal investigation triggered when the other student--chat transcripts in hand--contacted FBI agents in New York City about Madden’s role in the Gawker hack. The subsequent bureau probe, headed by Agent Olivia Olson, used an assortment of subpoenas, as well as motor vehicle and passport records to identify Madden as the hacker “Eekdacat.”

At 6:15 AM on June 29, 2011, Olson and other FBI agents searched Madden’s Troy home, and arrested him for the Gawker hack. The investigators seized all computer equipment in the residence and transported Madden to the bureau’s Manhattan office for questioning. Unaware of what their son was doing online, Madden’s parents were shocked by the nature of the FBI’s allegations. “They explained what occurred,” recalled Kenneth Madden, who said he was not knowledgeable enough about the online world to have monitored his son’s activities.

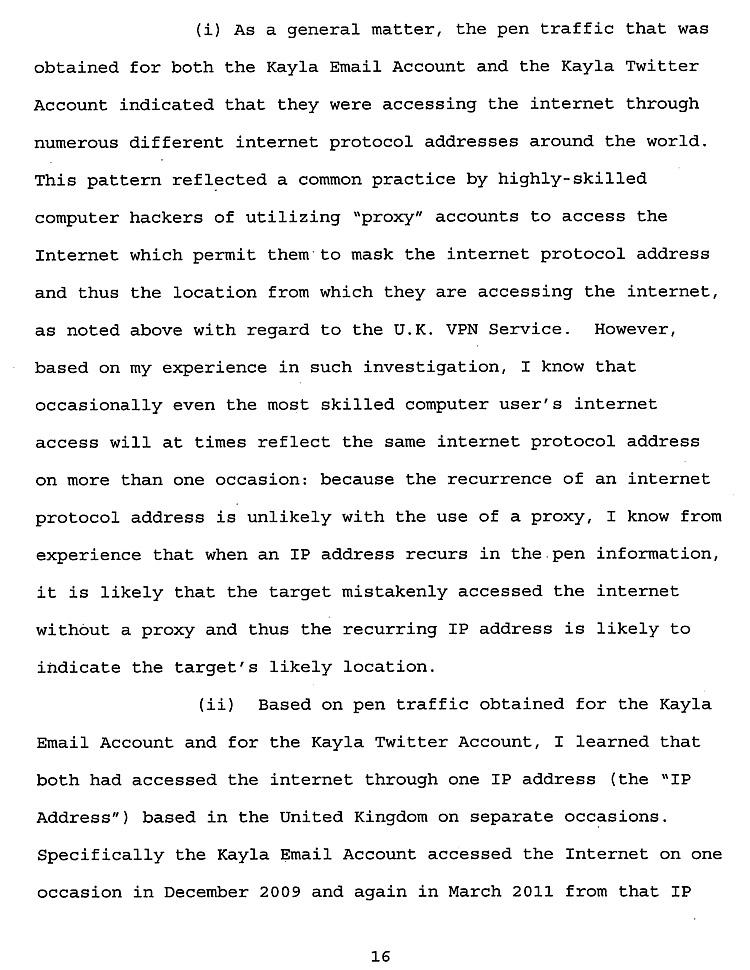

It was during FBI debriefings that Madden--who was not yet represented by an attorney--confessed to involvement in the Gawker breach, which he said was accomplished by a crew headed by a hacker known as “Kayla.” Madden said that “Kayla” provided him with “the stolen database of over one million usernames and encrypted passwords” and “tasked” him with decrypting the Gawker passwords. Madden  reported that he succeeded in cracking about 180,000 passwords.

reported that he succeeded in cracking about 180,000 passwords.

Madden told of communicating with “Kayla” intermittently over the prior year via instant messages and in an online forum. He also provided agents with his fellow hacker’s e-mail address, Twitter handle, and other contact information. It appears “Kayla” was the “someone big” to whom Madden referred when previously chatting about the Gawker hack.

At the time of Madden’s arrest, agents were already investigating “Kayla,” who was a Monsegur sidekick suspected of involvement in hacks that had victimized Fox Broadcasting, Sony Pictures, the Public Broadcasting Service, and other high profile corporate targets. “Kayla,” who claimed to be a teenage girl, was affiliated with several hacker groups, including Lulzsec, which disbanded on June 26, 2011 after a 50-day spree of hacking, defacement, and denial of service attacks.

Following his FBI debriefing--and nearly 12 hours after his arrest--Madden made an initial appearance in a closed federal courtroom in lower Manhattan. A U.S. District Court magistrate released Madden on a $100,000 bond secured by his father, and ordered that his Internet access would only be “via an FBI monitored laptop.”

When it came time for Madden to file a financial affidavit in support of his request for a court-appointed lawyer, he described himself as single, unemployed, and having no income. In a shaky scrawl, he signed the document “John Doe.”

In a post-arrest court filing, federal prosecutor Rosemary Nidiry reported that Madden “actively is cooperating with the Government and has indicated an intent to continue working proactively with the Government.” Madden, Nidiry said, provided investigators with “detailed information” about hacking suspects, adding that he could testify before a grand jury “for purposes of obtaining an indictment against the  defendant’s accomplices and other individuals identified by the defendant.”

defendant’s accomplices and other individuals identified by the defendant.”

Following Madden’s arrest, his lawyer requested a court-ordered mental competency exam for the hacker. As detailed in an FBI affidavit, that evaluation found that Madden “has a form of autism” which can affect his “social interaction and judgment, among other things.” But Agent Olson added that Madden appeared to be “highly-functioning in other areas, including the ability to recall information.” Madden, the investigator declared, was credible and his information had been corroborated.

So agents used Madden as the sole confidential witness in a series of search warrant and pen register applications targeting e-mail and Twitter accounts used by “Kayla.” In the sealed U.S. District Court filings, Madden is not identified by name, instead he is referred to as “CW-1” or “CW-2.” In sworn affidavits drafted a week after Madden’s arrest, Olson reported that the hacker “has attempted to cooperate with law enforcement in the hopes of reducing [his] sentencing liability.”

The warrants secured with the help of Madden proved key to law enforcement’s ability to identify the mysterious “Kayla,” the purported teen girl whose e-mails were filled with smiley faces (and whose security obsession and hacking exploits were legendary).

When agents first examined logs showing where the various accounts had been accessed from, it was clear that “Kayla” was using proxies to hide her true location, a standard hacker tactic. Hotmail and Twitter records showed that the respective accounts were accessed from a constantly changing stream of IP addresses that traced back to countries around the world.

But a close analysis of the IP records revealed that the master hacker had somehow slipped up.

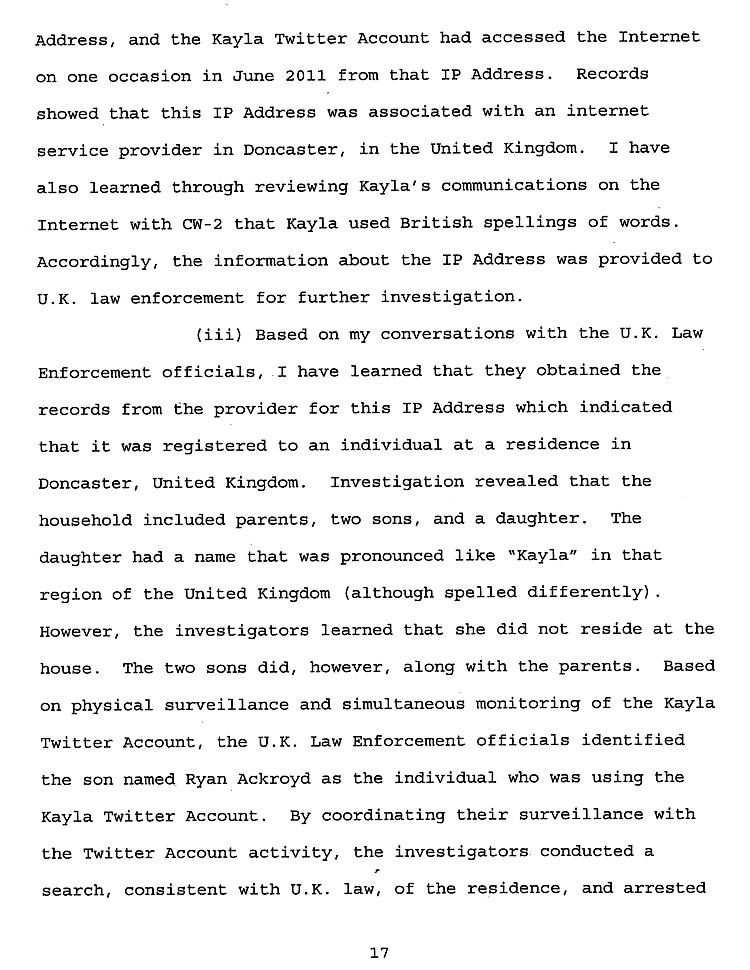

Since the recurrence of an individual IP address is unlikely with the use of a randomizing proxy, FBI agents alerted to a particular IP address that appeared three separate times in the documents. The address, which tracked to the United Kingdom, was used to access  “Kayla”’s e-mail account in December 2009 and March 2011. The same IP address also accessed the hacker’s Twitter account (@lolspoon) in June 2011.

“Kayla”’s e-mail account in December 2009 and March 2011. The same IP address also accessed the hacker’s Twitter account (@lolspoon) in June 2011.

The FBI provided the suspect IP address to British investigators, who tracked it to a home in the town of Doncaster in South Yorkshire. Following a period of surveillance and simultaneous monitoring of posts to the “Kayla” Twitter account, investigators burst into the residence and arrested Ryan Ackroyd, a former British soldier and Iraq War veteran. Ackroyd (seen at right) had borrowed his online handle from his sister, whose name “was pronounced like ‘Kayla’ in that region of the United Kingdom,” noted Agent Olson.

Ackroyd, now 27, was initially charged in Britain with launching hacking and denial of service attacks on UK targets that included the National Health Service and the country’s Serious Organised Crime Agency. He was aided in these illegal endeavors by several other British citizens who were fellow Lulzsec members.

Ackroyd pleaded guilty last year to the hacking campaign, for which he was sentenced to 30 months in prison.

In addition to the British case, Ackroyd and three codefendants (one Brit and two Irish citizens) were indicted in 2012 by a New York federal grand jury. The quartet was accused of carrying out a series of cyber attacks under the banners of Anonymous, Internet Feds, and Lulzsec. The Gawker intrusion, though, was not included among the alleged crimes cited in the two-count indictment. So Madden--who did not testify before the grand jury that indicted Ackroyd--remains the only hacker to have been arrested for that illegal operation.

When asked if federal prosecutors would eventually seek to have the imprisoned Ackroyd and his codefendants extradited to face the felony charges, a spokesperson for the U.S. Attorney’s Office in Manhattan would only say that “these cases are pending.”

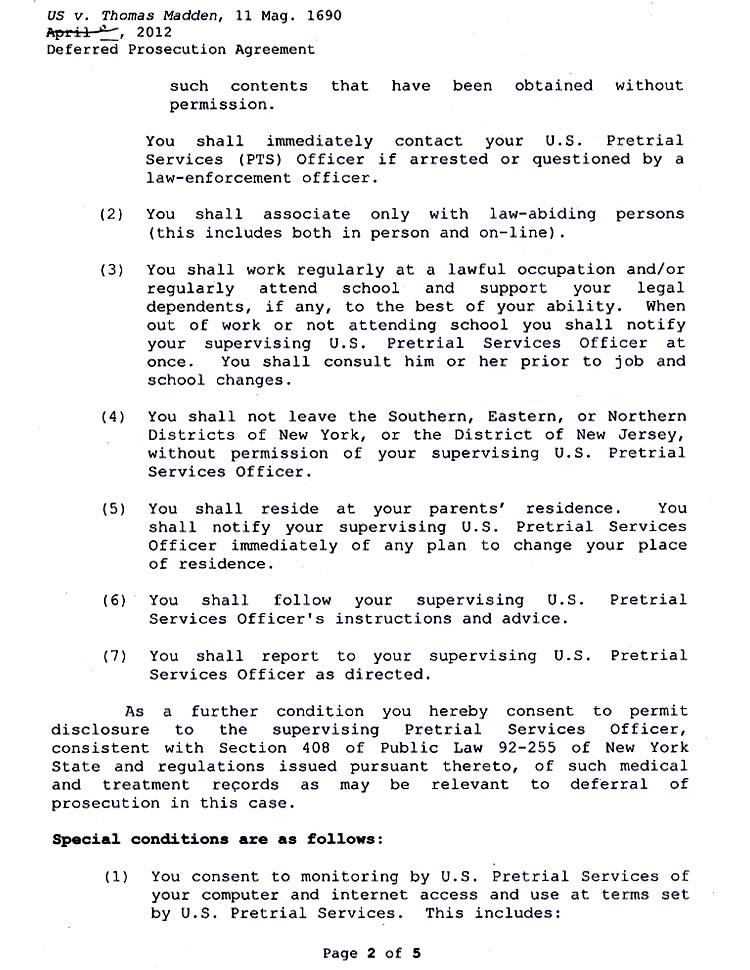

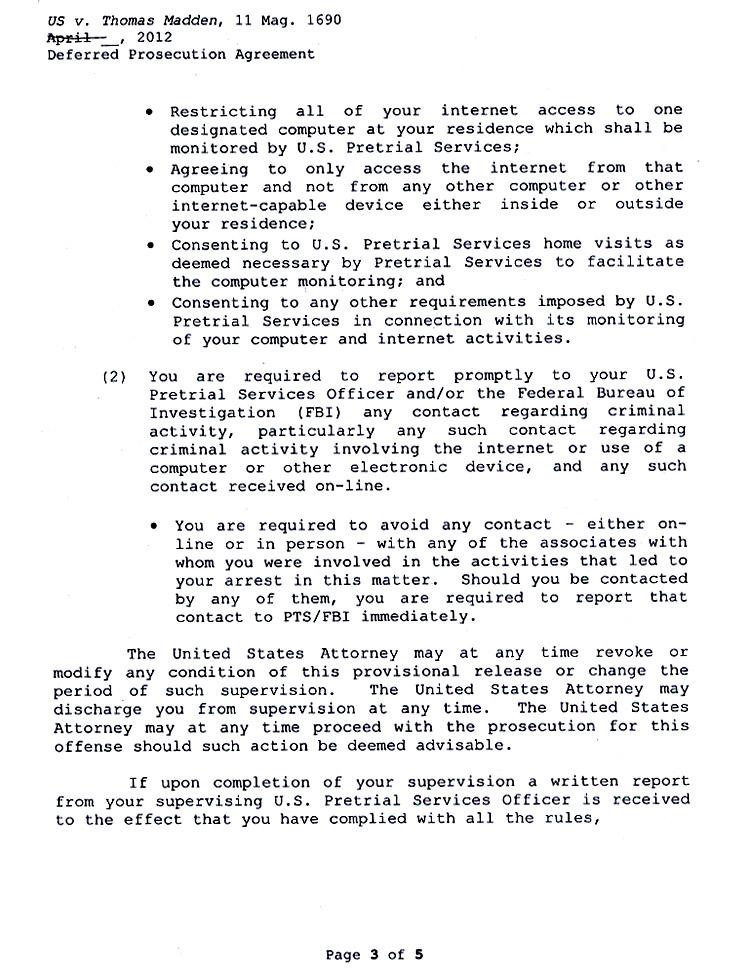

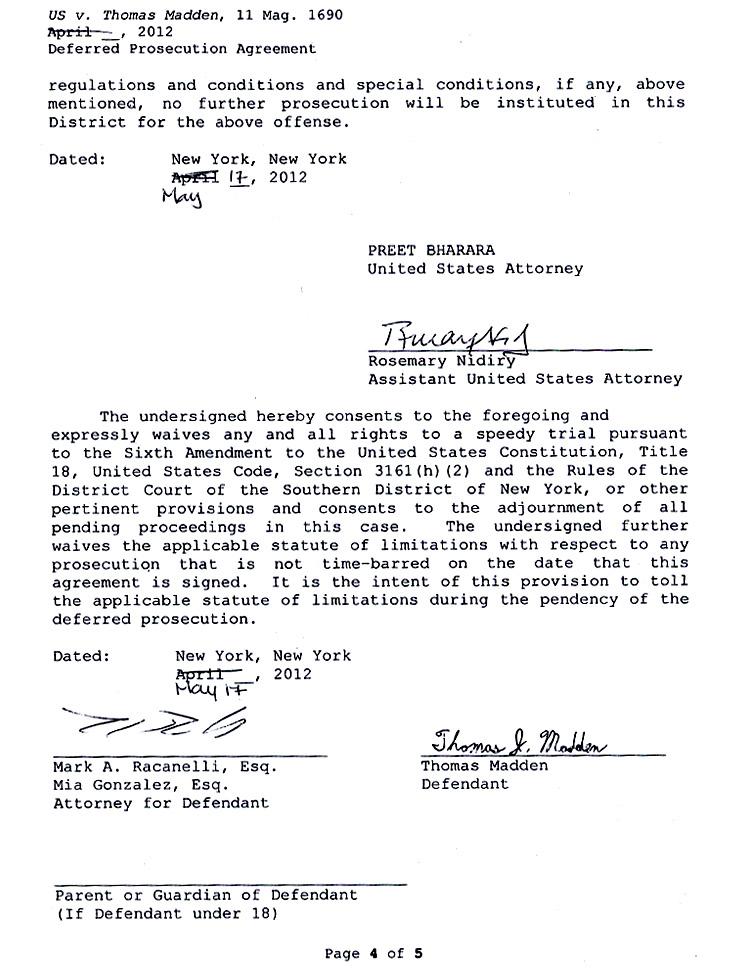

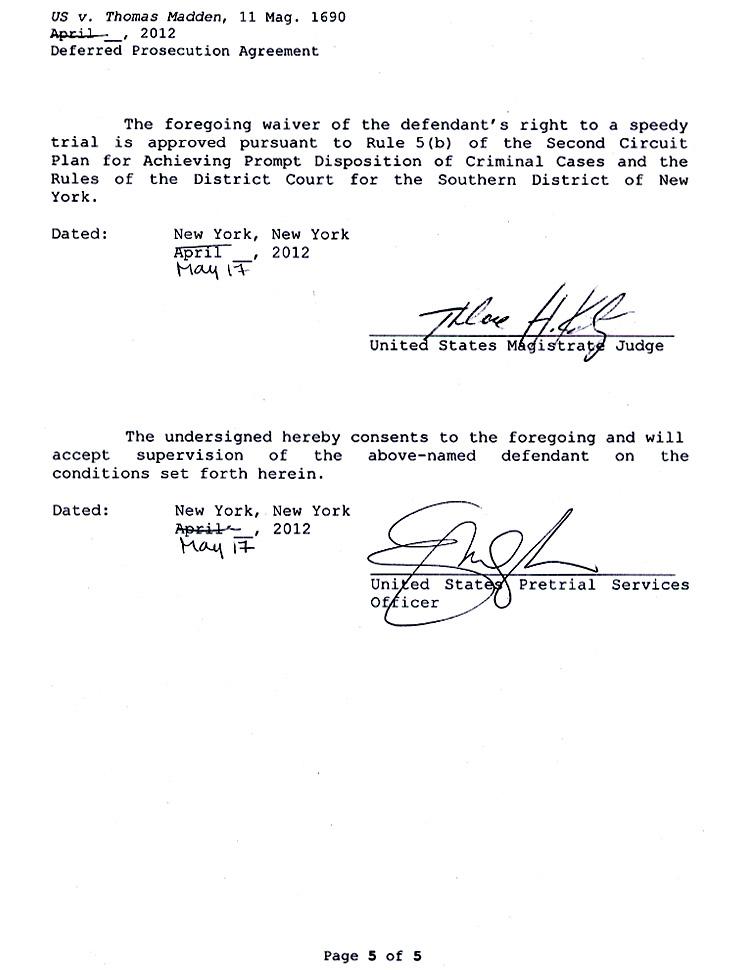

Two months after Ackroyd’s indictment, a “thorough investigation” by Justice Department officials concluded that the interests of the United States and Madden would “best be served by deferring prosecution” of the hacker’s criminal case. In November 2012, prosecutors formally dismissed the hacking charge against Madden, who, during the prior six months, stayed out of trouble and complied with terms stipulated in the deferred prosecution agreement struck with government lawyers.

Two months after Ackroyd’s indictment, a “thorough investigation” by Justice Department officials concluded that the interests of the United States and Madden would “best be served by deferring prosecution” of the hacker’s criminal case. In November 2012, prosecutors formally dismissed the hacking charge against Madden, who, during the prior six months, stayed out of trouble and complied with terms stipulated in the deferred prosecution agreement struck with government lawyers.

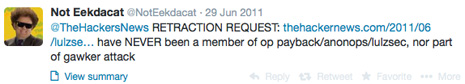

While Madden no longer faces any governmental restrictions on his Internet usage, he has maintained a low profile since prosecutors dropped the computer hacking case against him. He does not seem to have posted to his Twitter account (@NotEekdacat) since the day of his arrest.

Before the FBI banged on his door that morning, Madden sent a “RETRACTION REQUEST” tweet to a hacker news web site that had listed “Eekdacat” among the Lulzsec hacking team. “have NEVER been a member of op payback/anonops/lulzsec, nor part of gawker attack,” Madden declared. (28 pages)