Say It Ain’t So, Sergeant Joe

Army doctors criticized DiMaggio’s “defective attitude”

View Document

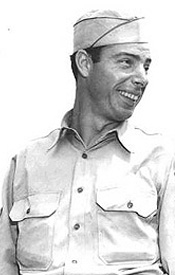

AUGUST 3--Despite having been aloof, irascible, and miserly, Joe DiMaggio remains one of history’s most beloved athletes, the Yankee Clipper who played on nine World Series champions, was voted into baseball’s Hall of Fame, married Marilyn Monroe, and, in retirement, pitched Mr. Coffee on TV.

But while his many accomplishments have been widely chronicled, one aspect of DiMaggio’s life has received little attention: the 2 ½ years he spent as an enlisted man in the mid-1940s. U.S. Army records obtained via a Freedom of Information Act request paint an unflattering portrait of DiMaggio as a deeply selfish soldier desperate for a wartime discharge.

Despite a cushy job as a physical instructor in the Army’s Special Services division, DiMaggio--who saw no combat, was never shipped overseas, and spent many months stationed in Hawaii--exhibited a “defective attitude toward the service” and a “conscious attitude of hostility and resistance” when it came to his Army duties.

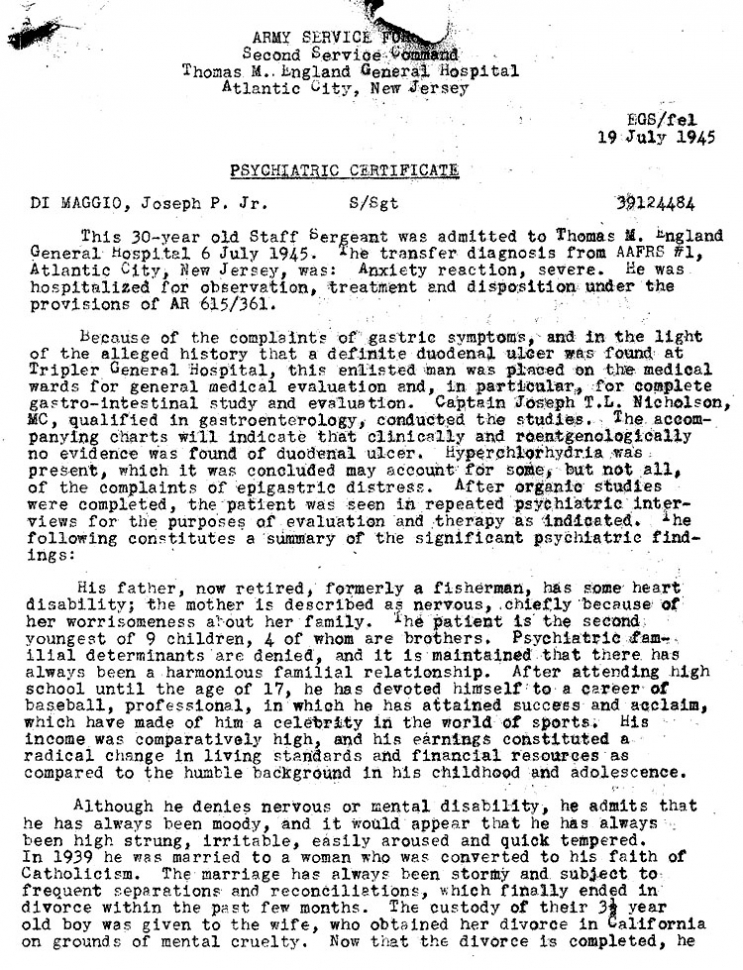

These withering critiques of DiMaggio came from two officers in the Army’s Medical Corps. In separate reports written shortly before DiMaggio’s discharge in September 1945, Major Emile G. Stoloff and Major William G. Barrett each portrayed DiMaggio, then 30, as someone whose “personal problems appeared to be of more consequence to him than his obligations to adjust to the demands of the service.” At the time, DiMaggio had just divorced his wife, who had custody of the couple’s young son. He was also distressed with his brother’s operation of a California restaurant in which he had invested, terming his sibling’s moves “a double-cross.”

problems appeared to be of more consequence to him than his obligations to adjust to the demands of the service.” At the time, DiMaggio had just divorced his wife, who had custody of the couple’s young son. He was also distressed with his brother’s operation of a California restaurant in which he had invested, terming his sibling’s moves “a double-cross.”

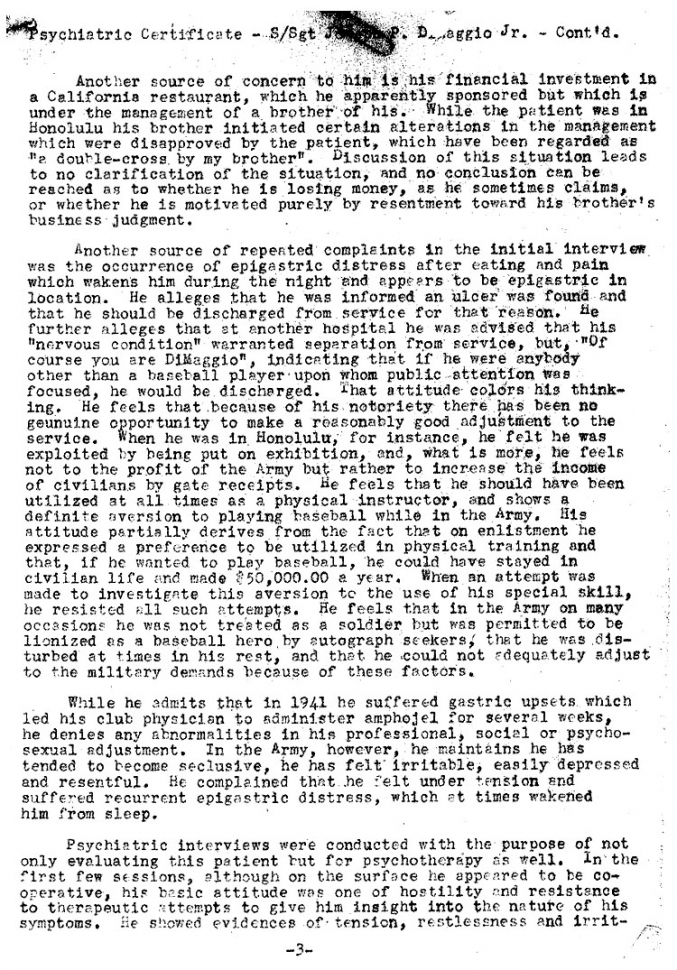

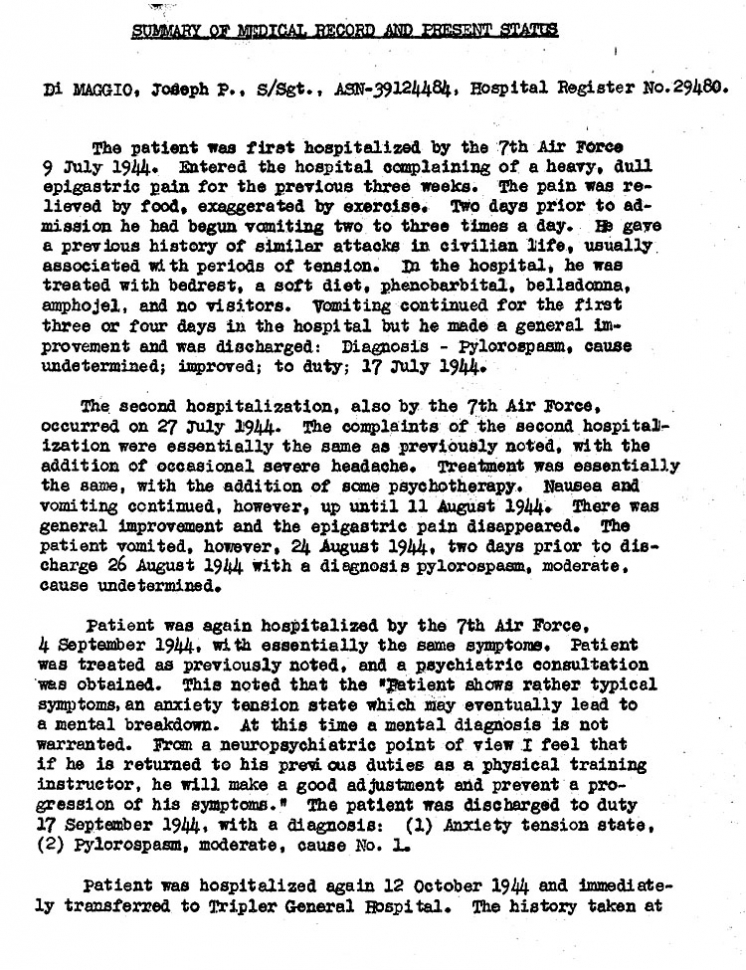

As seen in their reports (click on the thumbnail at left to view the documents), Stoloff, chief of neuropsychiatry, and Barrett detail DiMaggio’s frequent hospitalizations, brought about when the athlete would complain of abdominal pain. Though DiMaggio frequently contended that he suffered from an ulcer, Stoloff noted that “no evidence” was found to support this “alleged history.” Barrett referred to DiMaggio’s “natural tendency to protect himself by adopting those diagnoses and opinions which would lead to release from his present unhappy situation.”

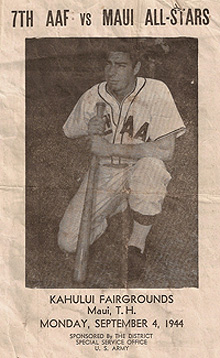

Citing his purported peptic ulcer and “nervous condition,” DiMaggio argued that these maladies warranted his immediate discharge. He was convinced, however, that military brass wanted to continue reaping the public relations benefits of having such a high profile athlete remain in the Army. With the country at war, DiMaggio, a staff sergeant, believed he had been “exploited” by the Army and made “an exhibitionist,” an apparent reference to the fact that DiMaggio played on Army baseball teams. As a result, he was “somewhat bitter about this discrimination,” Barrett reported.

During a psychiatric review, Stoloff noted, “an attempt was made to investigate” DiMaggio’s “aversion to the use of his special skill.” But when probed as to why baseball seemed so distasteful to him, DiMaggio “resisted all such attempts.” Similarly, when Army doctors conducted “psychiatric interviews…with the purpose of not only evaluating this patient but for psychotherapy as well,” reported Stoloff, DiMaggio was belligerent. His “basic attitude was one of hostility and resistance to therapeutic attempts to give him insight into the nature of his symptoms,” which were judge to be psychosomatic.

DiMaggio, Barrett reported, exhibited a “progressive maladaptation to a duty assignment as ideally suited as possible.” He added, however, that only “three hours of psychiatric study have been accomplished and it is not possible at this time to give more than a preliminary statement of the scope of the problem and possibilities for bringing about permanent improvement by means of psychotherapy.”

Stoloff concluded that, despite DiMaggio’s “conscious attitude of hostility and resistance toward doing so,” he could “be of further use to the military service” under certain conditions, including that he not be required to play baseball, sign autographs, or do interviews. DiMaggio, though, was discharged two months after Stoloff drafted his recommendations.

DiMaggio returned to the New York Yankees for the 1946 season and was named to the American League All-Star team, though his statistics reflected the three seasons he had missed. The following year, though, DiMaggio was named the league’s Most Valuable Player and the team won its 11th World Series title. (10 pages)

Comments (13)