Celeb Dirt To Be Sold? You Better Call Keith

A profile of the lawyer behind Trump "hush" deals

View Document

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

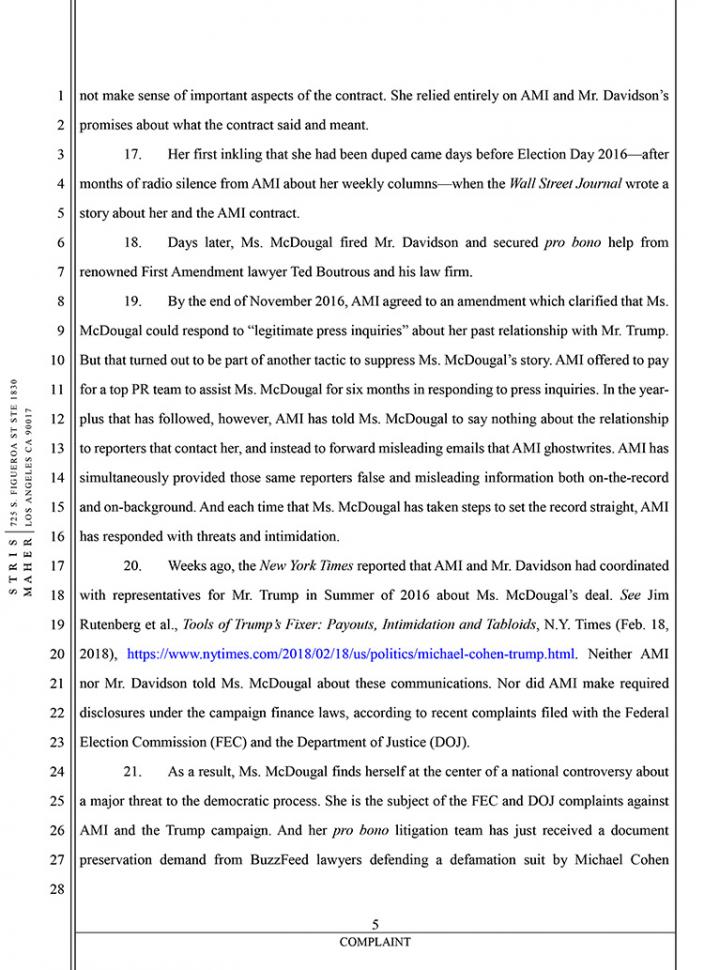

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

-

Keith Davidson

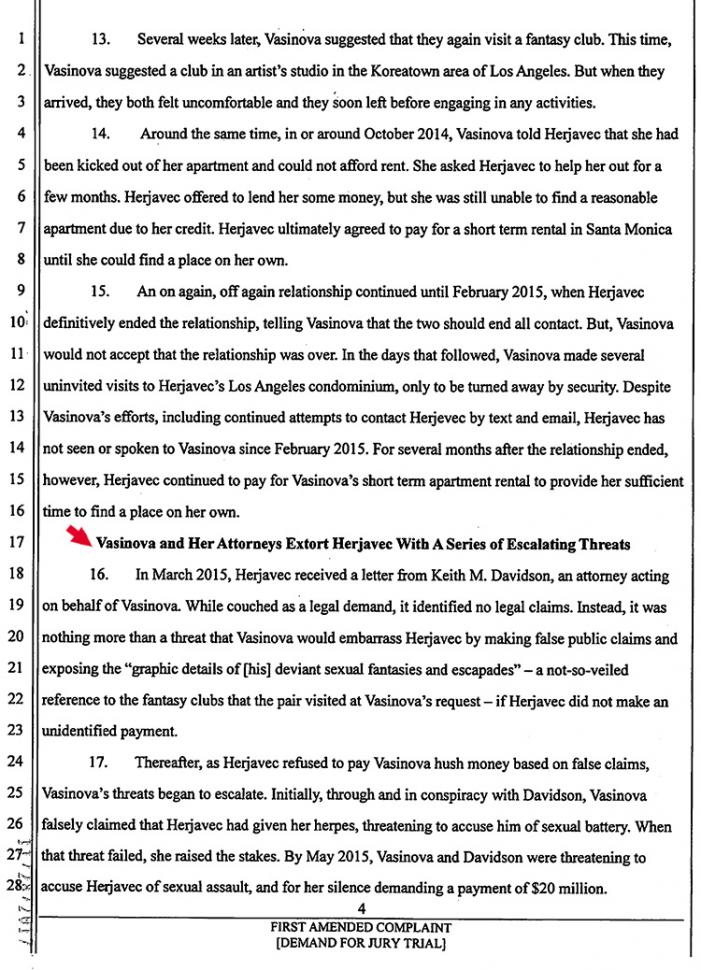

Another former porn performer, Gina Rodriguez, has been a leading source of celebrity case referrals to Davidson for more than a decade. Rodriguez now manages a slew of D-list celebrities and is an executive producer of a WE tv reality show chronicling the weight loss journey of June Shannon, the matriarch of the Georgia family featured on the TLC program “Here Comes Honey Boo Boo.” Rodriguez has specialized in wrangling mistresses (see: Woods, Tiger), porn actresses, and prostitutes  with stories to sell. Davidson estimated that Rodriguez, like Blatt, has referred him a maximum of 15 clients, including Stormy Daniels.

with stories to sell. Davidson estimated that Rodriguez, like Blatt, has referred him a maximum of 15 clients, including Stormy Daniels.

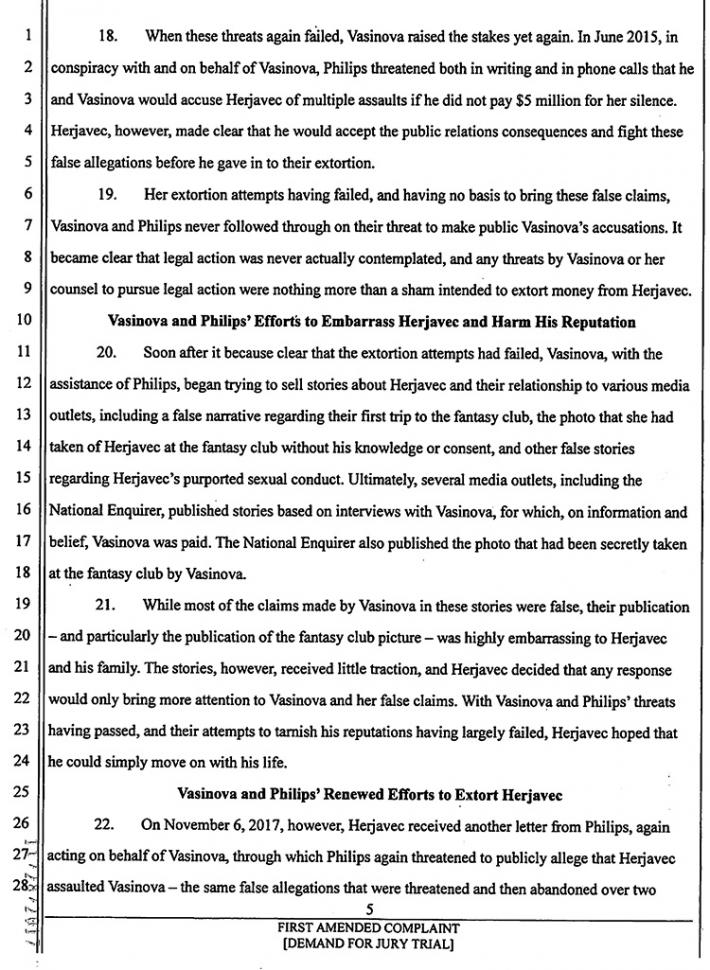

Montgomery was out of the porn business by the time the first checks from Sheen began arriving. She married De Anda in a Las Vegas ceremony in September 2013 and was living in a rented house in a gated development in Calabasas.

It was not long after the duo’s nuptials when they fired Davidson and replaced him with another L.A. personal injury attorney. The switch, however, would not impact Davidson’s continued collection of his share of the Sheen settlement.

Until it did.

Montgomery’s new lawyer, Sean Bral, conducted a review of the Sheen settlement documents and an audit of payments made by the actor (the Sheen funds went to Davidson’s client trust account, from which money was then distributed to Montgomery, Blatt, and Quinlan). Bral reported back to his clients that Davidson had mishandled proceeds from the Sheen settlement.

Bral then contacted Davidson and accused him of malpractice. Bral charged that Davidson had split his fee with non-lawyers, billed Montgomery more than the actual cost of her rehab stay, and received more money than he was  entitled to in the Sheen agreement. Davidson denied sharing his fee with Blatt and Quinlan. He told Bral that the rehab facility charged him more than the published rate because he paid Montgomery’s bill on an installment plan. But as for the claim that he received too much of his settlement share up front, Davidson had a problem.

entitled to in the Sheen agreement. Davidson denied sharing his fee with Blatt and Quinlan. He told Bral that the rehab facility charged him more than the published rate because he paid Montgomery’s bill on an installment plan. But as for the claim that he received too much of his settlement share up front, Davidson had a problem.

Bral noticed a discrepancy in the Sheen agreement and a related financial distribution sheet that Davidson had modified. Bral had an ethics opinion that contended Davidson should have afforded Montgomery the opportunity to consult independent counsel before agreeing to the modification (since it could amount to a conflict due to Davidson’s and Montgomery’s shared financial interests).

Though Davidson denied Bral’s malpractice claims, he agreed to disgorge funds he had received as part of the Sheen settlement. His capitulation to Montgomery’s legal demands also included the forgoing of all future payments. Like the celebrity settlements struck by Davidson himself, this one was done confidentially. Which surely did little to soften the blow the attorney suffered.

De Anda offered a blunt take on the predicament Davidson faced: “We had to threaten him to pay it all back or we were going to the Bar and get his license taken away.” Davidson’s decision to cede his share of the Sheen money was likely influenced by the fact that his law license had been suspended four years earlier and he wanted nothing to do with another  State Bar investigation.

State Bar investigation.

The tables had been turned on Davidson, who now was the one getting squeezed.

In fact, De Anda and Montgomery viewed their former attorney as something of an ATM. De Anda said, “When Charlie wouldn’t pay and we needed money we would just make Davidson pay us.” The lawyer not only shelled out money to Montgomery, but he ended up footing the bill for other expenses related to the Sheen case.

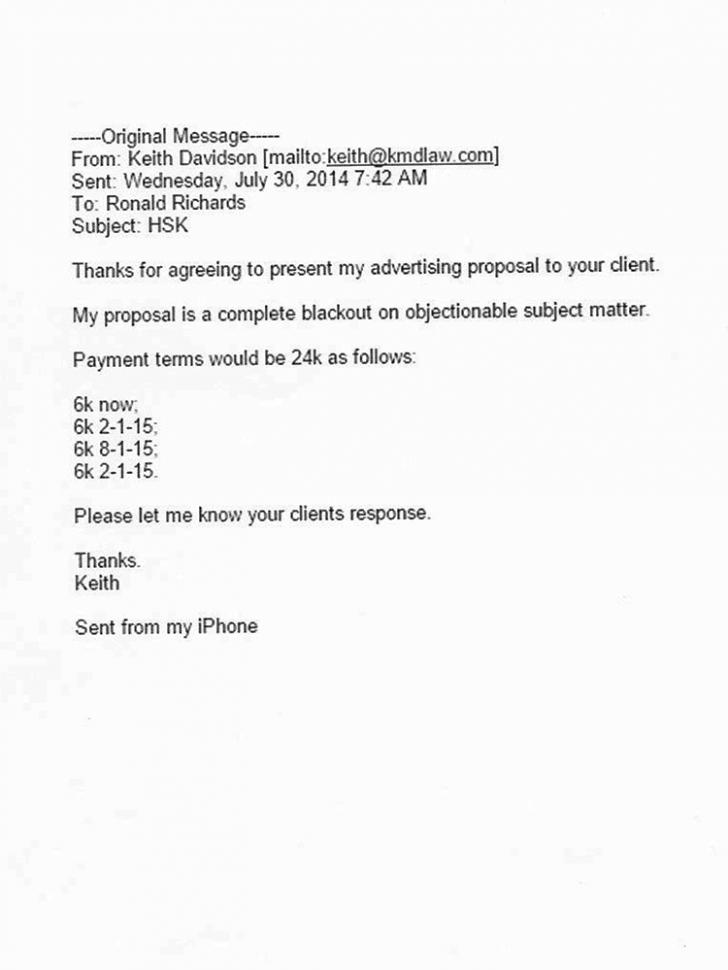

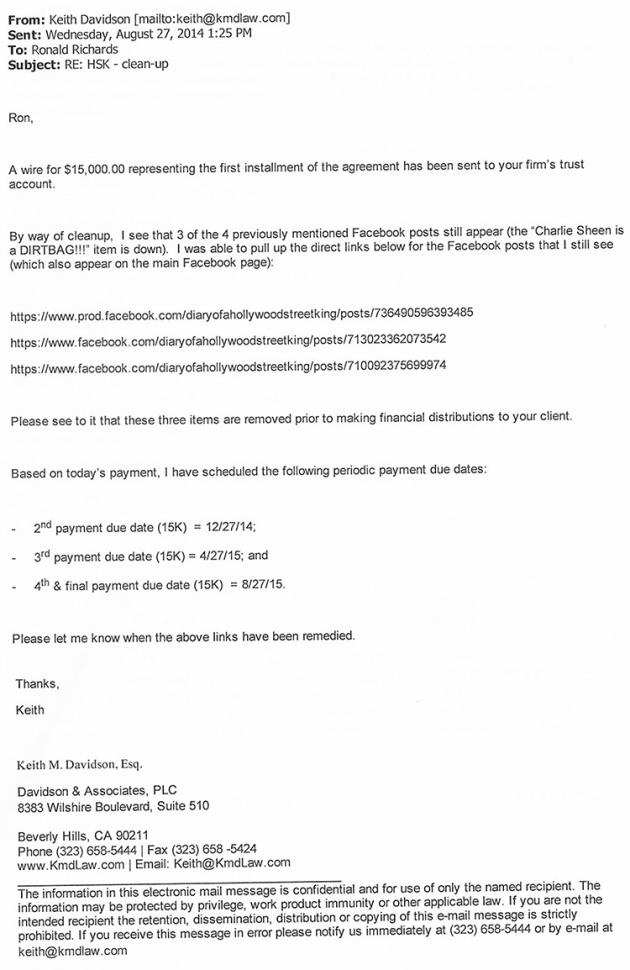

In mid-2014, Montgomery’s representatives became concerned about a series of posts on the Diary of a Hollywood Street King blog that reported she had received millions from the HIV-positive Sheen to “keep his medical business on the hush.” The suspected source was a DJ who procured sex partners for Sheen and became friends with Montgomery.

Though Davidson no longer had a financial stake in the Sheen settlement, he was directed by Montgomery & Co. to handle--and pay for--a remediation effort. The fear was that the blog items could be cited by Sheen’s lawyers as justification to cease payments based on a claim that the agreement’s confidentiality provisions were breached.

As detailed in a series of e-mails between Davidson and the blog's attorney, Davidson originally offered $24,000 for “a complete blackout on objectionable subject matter.” After negotiating for a month, Davidson agreed to pay $60,000 for the deletion of about 10 stories mentioning Sheen’s HIV status, his relationship with Montgomery, and his drug use. The offending stories included a dispatch headlined “Hollywood Whore Wrangler & HIV+ Tranny Could Be Charlie Sheen’s Worst Nightmare!”

The Sheen settlement was now costing Davidson money.

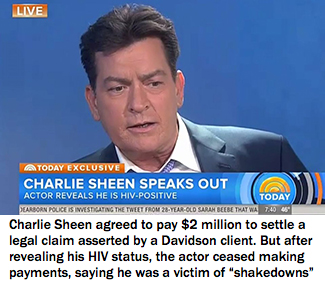

While payments to Davidson, Blatt, and Quinlan ended upon the lawyer’s firing, Montgomery continued receiving money from Sheen up until the star revealed that he was HIV positive during a November 2015 appearance on The Today Show. The actor claimed that he had been the victim of “shakedowns” by individuals threatening to disclose his HIV status. Asked if he would continue to make such hush money payments, Sheen replied, “Not after today, I’m not.”

The actor cast his admission as an effort to dispel the stigma associated with HIV. “I have a responsibility now to better myself and to help a lot of other people,” Sheen said. Privately, however, the performer raged, blaming Montgomery for leaking word of his HIV status. In a text to a mutual friend, Sheen wrote, “I fucking despise Kira and what she’s done to me and my family.” Her actions, Sheen added, were “beyond treason.”

As a result of Sheen’s subsequent claim that Montgomery, 30, violated terms of the settlement, the parties entered into a confidential arbitration proceeding. Montgomery, now the  mother of two young children, has forwarded her hefty bills for that arbitration to Davidson for payment.

mother of two young children, has forwarded her hefty bills for that arbitration to Davidson for payment.

Quinlan, who estimated that he got around $30,000 from the Sheen settlement, said that he had little recourse when Davidson ceased paying him. “It was kind of a shady deal,” Quinlan said, adding that his arrangement with the attorney was not “a normal above-the-board business thing where you can take it to court.” Still, Quinlan did not blame Davidson. “I honestly think he woulda kept paying it,” Quinlan said, but “his money stopped coming in.”

Quinlan then opined on the disparity between Davidson--an avid golfer who is a member of the exclusive Sherwood Country Club--and the louche characters he often represents in celebrity cases: “The funny thing is that his personality is the exact opposite. He’s a total fucking square. He’s married with kids and goes to a country club. He’s like the exact opposite of what his whoring skills are.”

Quinlan continued, “Keith’s actually pretty cool. He’s actually a pretty decent dude. He’s a shady lawyer but he’s a decent guy.”

To be clear: This was a compliment on Quinlan’s part. A Hollywood kind of compliment.

* * *

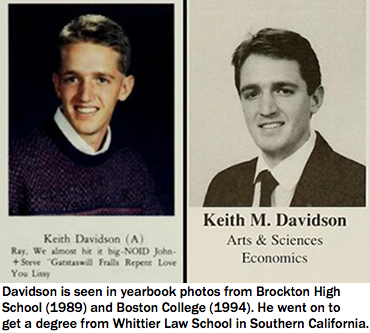

Davidson is a native of Brockton, Massachusetts, where his large Irish-American family includes several generations of firefighters. About an hour south of Boston, Brockton is known as the “City of Champions” since it was the home of boxing legends like Rocky Marciano, the undefeated heavyweight champion, and “Marvelous” Marvin Hagler, who held the middleweight title for seven years during the 1980s. Davidson recalled in an interview how he and his friends--in a Rocky-esque moment--would chase after Hagler as the boxer did roadwork on the Brockton streets.

After graduating Brockton High School in 1989, Davidson attended Boston College, where he studied economics. Though he could not afford BC housing, Davidson still lived on campus, thanks to a high school buddy who welcomed him as an unofficial roommate in a six-man dormitory suite. Davidson’s nest was an 8 x 10 space that had been used as a closet. Davidson graduated BC in 1994 and worked for the Massachusetts state legislature and the Plymouth County District Attorney’s Office before his acceptance to Whittier Law School in Costa Mesa, California. Whittier, a bottom-tier school, last year announced that it would be closing in the face of financial problems and a disastrous bar passage rate (22 percent).

In December 2000, Davidson was licensed to practice after passing the notoriously difficult California bar exam (from that point forward, he has worked as a solo practitioner). As a young attorney, Davidson represented all types of criminal defendants, from drunk drivers to accused killers. He sounded wistful while recounting how he secured an acquittal for a  young woman charged with murder. The defendant’s impoverished mother, Davidson said, struggled to pay him and sometimes did so with rolls of quarters. While describing his early days as a defense lawyer, Davidson recalled receiving a note from an aunt, who is a nun. She wrote to remind her nephew to always remember the plight of the poor.

young woman charged with murder. The defendant’s impoverished mother, Davidson said, struggled to pay him and sometimes did so with rolls of quarters. While describing his early days as a defense lawyer, Davidson recalled receiving a note from an aunt, who is a nun. She wrote to remind her nephew to always remember the plight of the poor.

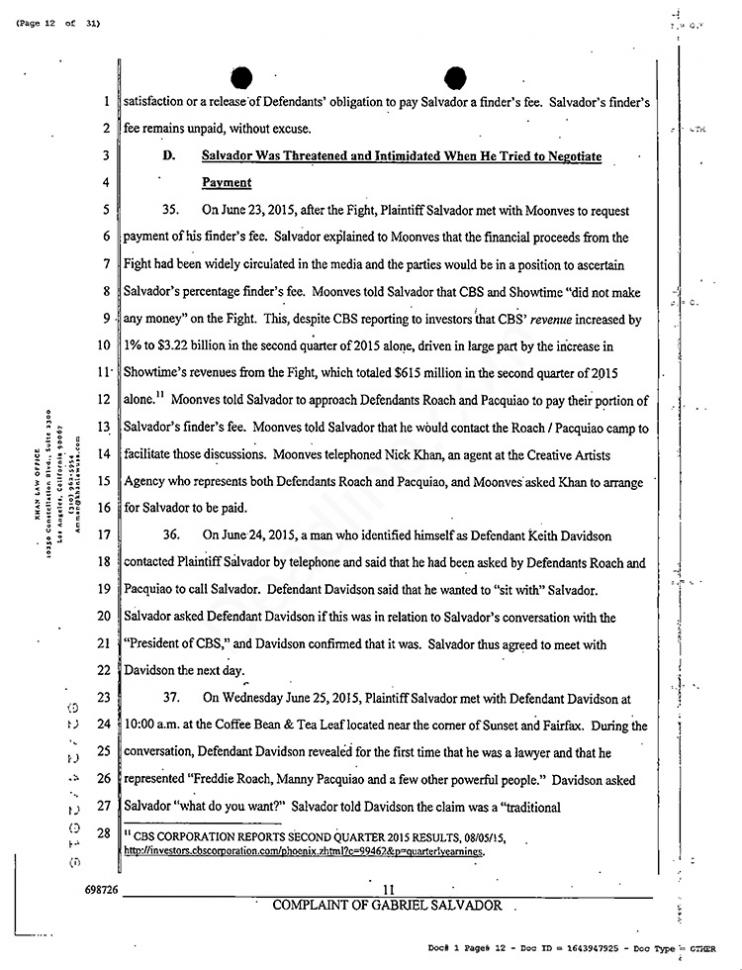

In addition to his law practice, Davidson was involved in the management of professional boxers. Through a mutual friend, he met trainer Freddie Roach after moving to Los Angeles. Roach, who grew up about 15 miles from Davidson’s hometown, was instrumental in helping the attorney become part of the management team for fighters like Manny Pacquiao and James Toney.

Though he no longer manages boxers, Davidson remains close to Roach and, according to a source, once even quashed a sex tape for the trainer. Asked about this, Davidson took a long pause and answered, “Freddie’s a single guy, he’s charming as hell,” adding that the wealthy Roach was a “target.” Roach and Davidson are codefendants in a lawsuit filed by Gabriel Rueda, a Los Angeles waiter who contends that he is entitled to a multimillion dollar finder’s fee for his role in arranging Pacquiao’s 2015 fight against Floyd Mayweather. Rueda, who also goes by Gabriel Salvador, accuses Davidson of trying to extort him in a bid to force the acceptance of a lowball settlement offer. Davidson denies Rueda’s charges.

Davidson’s practice would eventually transition into the handling of civil matters, primarily personal injury cases taken on a contingency fee basis. The nature of Davidson’s civil caseload is reflected in the source code of his web site, which includes tags like “herpes,” and “dental malpractice.” He has also registered web domains like birthinjurysupport.com, burnresources.com, drowningsupport.com, mvcrash.com, and teslaclassaction.com. Additionally, Davidson registered charliesheenlawsuit.com the day before the actor disclosed his HIV status. A cached version of Davidson’s web site from 2006 shows that the lawyer claimed his firm was “staffed with only the best and brightest talent in the legal field” and that “each of our employees possess the perfect mixture of mental and physical toughness.” Davidson--who only employed a paralegal, Vilma Duarte--also declared that, “We maintain not only trained legal minds, but a staff of medical doctors, registered nurses, and psychiatrists as well.”

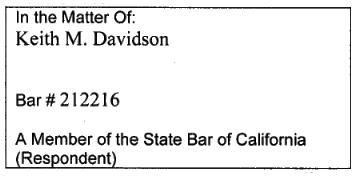

Despite overheated claims of unparalleled proficiency and exacting legal standards, Davidson was the subject of three separate complaints lodged with the State Bar of California. He was accused of assorted professional misconduct, including mishandling a lawsuit filed on behalf of an L.A. couple who sued a state hospital for the mentally ill over complications  their son suffered from a brain injury. Davidson failed to show for court hearings in that medical malpractice case, prompting a judge to dismiss the matter (news that the lawyer did not share until confronted by his clients weeks later).

their son suffered from a brain injury. Davidson failed to show for court hearings in that medical malpractice case, prompting a judge to dismiss the matter (news that the lawyer did not share until confronted by his clients weeks later).

Davidson would also face a lawsuit filed by an ex-client who accused him of professional negligence and alleged that he included “materially false allegations” in a lawsuit he filed on her behalf against the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department. The woman, who had signed a contingency fee retainer with Davidson, alleged that when the attorney determined that her “medical damages were not as once originally believed,” he “decided not to put any time or money into the case,” thereby placing his financial interests above hers. Davidson eventually paid the client, an elderly Korean-American woman, to settle the lawsuit, which was not part of the state disciplinary action.

Charged with repeatedly failing to “perform legal services with competence” and willfully violating professional conduct rules, Davidson “recognized his wrongdoing and admitted culpability,” according to a 2010 State Bar filing.

Months before the tenth anniversary of his bar admittance, Davidson was hit with a two-year suspension, placed on probation for three years, and ordered to attend State Bar Ethics School. As part of his probation, Davidson was required to submit sworn quarterly reports confirming his compliance with the State Bar Act and professional conduct rules. Since Davidson had not been previously disciplined--and he provided character letters attesting to his “overall honesty”--the two-year suspension was stayed in favor of a 90-day period in which he was barred from practicing law.

As it turned out, Davidson actually got lucky. Disciplinary officials were unaware of another matter from the same period that, if discovered, might have cost him his license.

* * *

Davidson’s first celebrity case involved someone trying to get rich off the back of Paris Hilton. That someone was Davidson himself.

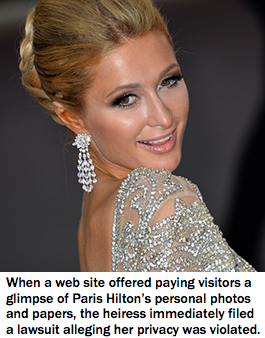

In November 2005, a large cache of Hilton’s belongings were purchased at auction for $2775 at a Public Storage location in Culver City. The heiress’s representatives had failed to pay an outstanding $208 bill, so the contents of her locker--personal diaries, racy videos, nude photos, medical and financial records, clothing--were sold off “Storage Wars”-style.

Nabila Haniss, the woman who purchased the Hilton material, later stated in a sworn court affidavit that she sold the items for $150,000. Haniss’s lawyer told ABC News that his client did not know the identity of the purchaser, who “came with a bag of cash and she handed him” Hilton’s property.

In January 2007, the web site Paris Exposed (parisexposed.com) launched, offering a massive trove of Hilton’s belongings. “Never Before in the History of the World has a Celebrity Been Exposed Like This! This is the Stuff the Public Was Never Meant to See,” the site screamed. For $39.97, visitors could browse through 25,000 personal photos and read Hilton’s journals with “her private thoughts about sex, dating, drugs and boyfriends.” The slick, professionally produced site offered Hilton’s medical records and promised to answer such  questions as “Did she really give Cher’s son genital herpes?”

questions as “Did she really give Cher’s son genital herpes?”

Within days of Paris Exposed appearing online, Hilton’s lawyers filed a federal lawsuit accusing the site of copyright infringement and invasion of privacy. A Hilton attorney declared that it was "one of the single most egregious and reprehensible invasions of privacy ever committed against an individual."

A United States District Court judge agreed and issued a February 20 injunction barring Paris Exposed from continuing to publish a wide range of the Hilton material. The only defendant cited in Judge George King’s order was Bardia Persa, who was named in the site’s domain registration. Hilton’s counsel believed that Persa, whose address was a post office box in Panama City, Panama, was a fictitious individual. Armed with the injunction, Hilton’s lawyers succeeded in getting Paris Exposed removed from its servers, which were located at a hosting firm 30 miles outside of Amsterdam in the Netherlands.

For four months, the Hilton material remained offline. Then, in early-June, Paris Exposed reappeared, offering a $19.97 “relaunch special” subscription. Flouting the standing court injunction, the site’s front page brayed, “The City that let OJ Simpson go free quickly reacted to Ms. Hilton’s request and forced ParisExposed.com offline for Privacy and Copyright Issues.” Taunting the court and Hilton’s counsel, the site reported that it was now hosted “on hundreds of servers placed around the world behind secure firewalls in jurisdictions that will not bow to the heiress and her overpaid legal team.” According to sources and server records obtained by TSG, the site’s relaunch was shepherded by a programmer whose prior experience included work for the sites pornojunkies.com and transexualworld.com.

The Paris Exposed relaunch was remarkably brazen and prompted a Hilton lawyer to remark in a court filing that, “even an injunction issued by a United States District Court is insufficient to deter” the site’s operators.

Hilton’s attorneys returned to court and sued several new defendants, including Green Brothers Limited, an offshore entity that was the web site’s new registrant. The shell company, formed on the Caribbean island of St. Kitts, was represented by Davidson.

Asked about his role with Paris Exposed, Davidson told TSG, “I represented someone who was the content owner at one point.” Asked who that was, he replied, “I can’t really say.”

While Davidson sought to minimize his role with the outlaw web site, two sources with detailed knowledge of the creation of Paris Exposed described the attorney as the driving force behind the business. “All of the coordination efforts were managed by Mr. Davidson,” said a former Paris Exposed staffer. “I never met anyone else who was coordinating things.”

According to the sources, Davidson, who has no technical expertise, recruited an acquaintance, digital entrepreneur Andrew Maltin, to hire the team of programmers and designers  who spent months digitizing the Hilton material and building the web site. The group worked from a rented L.A. home, where some coders bunked in the run-up to the site’s launch. Two months before Paris Exposed debuted, a Davidson deputy flew to Amsterdam to set up the site’s servers in the city of Haarlem.

who spent months digitizing the Hilton material and building the web site. The group worked from a rented L.A. home, where some coders bunked in the run-up to the site’s launch. Two months before Paris Exposed debuted, a Davidson deputy flew to Amsterdam to set up the site’s servers in the city of Haarlem.

One source recalled that Davidson traveled to St. Kitts to establish banking and credit card processing accounts. The second source said that Davidson had a controlling interest in the business, while Maltin had a smaller equity share. Both sources believe that Davidson was responsible for securing the capital used to purchase the Hilton trove, but they were unclear whether he found an investor or put up the money himself.

When Davidson was confronted with the source accounts of his managerial role with Paris Exposed, his halting answers were punctuated by long pauses. Asked if he traveled to St. Kitts to form the shell company and establish business accounts, Davidson answered, “I don’t know, let me get back to you on that one.” As for whether he owned a piece of the web site, Davidson said, “I don’t believe so, no.” Did he recruit Maltin and oversee the web site’s development? Davidson replied that he would also need additional time to answer that question.

More importantly, as to the matter of an attorney flouting a federal court order, Davidson went mute. Asked if his silence equated to a “Still want to think about it,” Davidson said, “Yes.” The lawyer subsequently declined to further address any TSG questions about his role with Paris Exposed.

The web site has been offline for years and the parisexposed.com domain is parked at an L.A. web hosting firm. The site’s administrative contact, who appears to be fictitious, is listed at a nonexistent address in Toronto, Canada.

* * *

Davidson was first accused of being a shakedown artist in October 2010. And then again 46 days later.

In an invasion of privacy lawsuit brought by Tila Tequila, the model/reality TV star alleged that Davidson, who represented a former boyfriend of Tequila’s, threatened to market a sex tape the couple filmed years earlier. Tequila charged that Davidson warned that he would sell the video “overseas” if she did not consent to its distribution.

A rogue foreign sale of the sex tape would result in no profits for Tequila. But if she agreed to the video’s distribution (like Paris Hilton and Kim Kardashian had done before), Tequila would get a cut of the proceeds. Tequila, however, had no interest in the home video’s distribution. She had filmed a pair of yet-to-be-released pornos for Vivid Entertainment and  did not want a competing title on the market.

did not want a competing title on the market.

“I’m not a high pressure guy like, ‘Buy this or else. Or if you don’t buy this, we’re gonna take it offshore,’” Davidson said in an interview. “This is not something I do.”

As with many of Davidson’s celebrity cases, Blatt was responsible for putting the attorney together with Tequila’s former beau, musician Francis Falls (Davidson, Blatt, and Falls were codefendants in the Tequila lawsuit). Blatt had tried to sell the tape to Vivid, but acknowledged that he had not secured Tequila’s consent for its distribution. According to Steve Hirsch, Vivid’s CEO, Blatt added that there were “ways to get around” Tequila’s intransigence, including uploading the footage to servers in Canada or China.

Tequila’s allegations against Davidson came at a sensitive time for the attorney, who was in the middle of his 90-day suspension for professional misconduct. So Davidson moved quickly to extricate himself from the lawsuit.

In an e-mail sent to Tequila’s attorney two weeks after the complaint was filed, Davidson wrote that he had personally acquired the copyright to the Tequila sex tape and was ready to turn it over to the model in exchange for dismissal of the lawsuit. But he required something else: Language in the settlement agreement needed to state that no attorney involved in the matter “has breached any ethical duty...including without limitation any application of the California Rules of Professional Conduct.”

Asked how he obtained the copyright from his client, Davidson replied, “I don’t recall. I don’t recall if I paid him a dollar or $500. I have no idea.” He added, “So I acquired the copyright and was willing to give it back to her for nothing. I thought that it was probably an admirable thing to do and a way to get rid of the whole case.”