A Million Little Lies

Exposing James Frey's Fiction Addiction

View Document

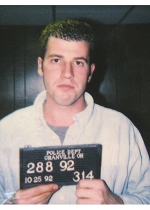

James Frey Granville Police Report

-

James Frey Granville Police Report

-

James Frey Granville Police Report

-

James Frey Granville Police Report

-

James Frey Granville Police Report

-

James Frey Granville Police Report

-

James Frey Granville Police Report

James Frey Legal Threat Letter

-

James Frey Legal Threat Letter

-

James Frey Legal Threat Letter

-

James Frey Legal Threat Letter

-

James Frey Legal Threat Letter

-

James Frey Legal Threat Letter

Granville Police Denison Drug Investigation (Frey)

-

Granville Police Denison Drug Investigation (Frey)

-

Granville Police Denison Drug Investigation (Frey)

-

Granville Police Denison Drug Investigation (Frey)

-

Granville Police Denison Drug Investigation (Frey)

-

Granville Police Denison Drug Investigation (Frey)

-

Granville Police Denison Drug Investigation (Frey)

-

Granville Police Denison Drug Investigation (Frey)

-

Granville Police Denison Drug Investigation (Frey)

-

Granville Police Denison Drug Investigation (Frey)

-

Granville Police Denison Drug Investigation (Frey)

-

Granville Police Denison Drug Investigation (Frey)

-

Granville Police Denison Drug Investigation (Frey)

-

Granville Police Denison Drug Investigation (Frey)

St. Joseph Accident Report (James Frey)

-

St. Joseph Accident Report (James Frey)

-

St. Joseph Accident Report (James Frey)

-

St. Joseph Accident Report (James Frey)

-

St. Joseph Accident Report (James Frey)

-

St. Joseph Accident Report (James Frey)

-

St. Joseph Accident Report (James Frey)

-

St. Joseph Accident Report (James Frey)

-

St. Joseph Accident Report (James Frey)

-

St. Joseph Accident Report (James Frey)

-

St. Joseph Accident Report (James Frey)

-

St. Joseph Accident Report (James Frey)

-

St. Joseph Accident Report (James Frey)

-

St. Joseph Accident Report (James Frey)

-

St. Joseph Accident Report (James Frey)

-

St. Joseph Accident Report (James Frey)

-

St. Joseph Accident Report (James Frey)

But he has demonstrably fabricated key parts of the book, which could--and probably should--cause a discerning reader (and Winfrey has ushered millions of them Frey's way) to wonder what is true in "A Million Little Pieces" and its sequel, "My Friend Leonard."

When TSG confronted him Friday (1/6) afternoon with our findings, Frey refused to address the significant conflicts we discovered between his published accounts and those contained in various police reports. When we suggested that he might owe millions of readers and Winfrey fans an explanation for these discrepancies, Frey, now a publishing powerhouse, replied, "There's nothing at this point can come out of this conversation that, that is good for me."

It was the third time since December 1 that we had spoken with Frey, who told us Friday that our second interview with him, on December 14, had left him so "rattled" that he went out and hired Los Angeles attorney Martin Singer, whose law firm handles litigation matters for A-list stars like Jennifer Aniston, Catherine Zeta-Jones, and Britney Spears. While saying that he had initially asked his counsel not to send us a pre-publication legal letter, Frey apparently relented late Friday night. That's when Singer e-mailed us a five-page letter threatening a lawsuit (and the prospect of millions in damages) if we published a story stating that Frey was "a liar and/or that he fabricated or falsified background as reflected in 'A Million Little Pieces.'"

On Saturday evening, Frey published on his web site an e-mail we sent him earlier in the day requesting a final interview. That TSG letter also detailed many topics we discussed with him in our first two interviews, both of which were off the record. We consider this preemptive strike on Frey's part as a waiver of confidentiality and, as such, this story will include some of his remarks during those sessions, which totaled about 90 minutes. Frey explained that he was posting our letter to inform his fans of the "latest attempt to discredit me...So let the haters hate, let the doubters doubt, I stand by my book, and my life, and I won't dignify this bullshit with any sort of further response."

This was, Frey wrote, "an effort to be consistent with my policy of openness and transparency." Strangely, this policy seemed to have lapsed in recent weeks when Frey, in interviews with TSG, repeatedly refused to talk on the record about various matters, declined our request to review "court" and "criminal" records he has said he possesses, and continued to peddle book tales directly contradicted by various law enforcement records and officials.

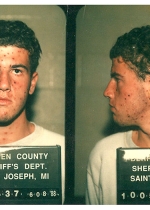

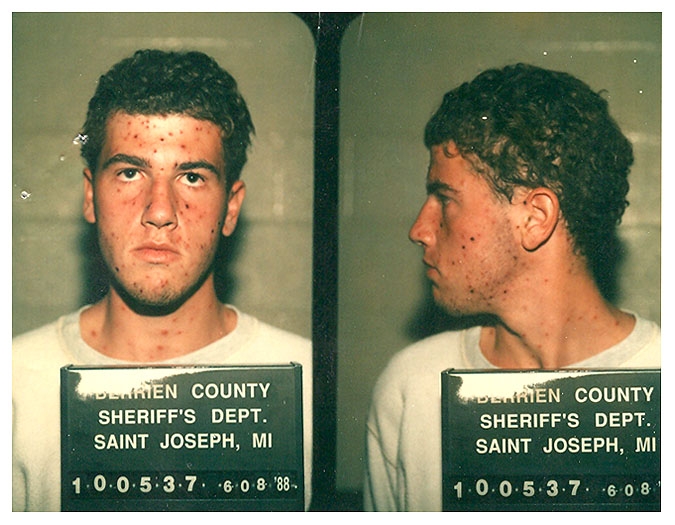

But during these interviews, Frey did, for the first time, admit that he had embellished central details of his criminal career and purported incarceration for "obvious dramatic reasons" in the nonfiction work. He also admitted to taking steps, around the time "A Million Little Pieces" was published in hardcover in 2003, to legally expunge court records related to the seemingly most egregious criminal activity of his lifetime. That episode--a violent, crack-fueled confrontation with Ohio cops that resulted in a passel of serious felony charges--is a crucial moment in "A Million Little Pieces," serving as a narrative maypole around which many other key dramatic scenes revolve and depend upon for their suspense and conflict. Frey has repeatedly asserted in press interviews that the book is "all true" and he told Winfrey, "I think I wrote about the events in the book truly and honestly and accurately."

The author told us that he had the court records purged in a bid to "erect walls around myself." Referring to our inquiries about his past criminal career, Frey noted, "I wanted to put up walls as much as I possibly could, frankly, to avoid situations like this." The walls, he added, served to "keep people away from me and to keep people away from my private business." So much for the openness and transparency.

So why would a man who spends 430 pages chronicling every grimy and repulsive detail of his formerly debased life (and then goes on to talk about it nonstop for 2-1/2 years in interviews with everybody from bloggers to Oprah herself) need to wall off the details of a decade-old arrest? When you spend paragraphs describing the viscosity of your own vomit, your sexual failings, and the nightmare of shitting blood daily, who knew bashfulness was still possible, especially from a guy who wears the tattooed acronym FTBSITTTD (Fuck The Bullshit It's Time To Throw Down).

We discovered the answer to that question in the basement of an Ohio police headquarters, where Frey & Co. failed to expunge the single remaining document that provides a contemporaneous account of his watershed felonious spree.

![]()

Since the book's 2003 publication (the $14.95 paperback was issued last summer by Anchor Books), Frey has defended "A Million Little Pieces" against critic claims that parts of the book rang untrue. In a New York Times review, Janet Maslin mocked the author--a former alcoholic who has rejected the precepts of Alcoholics Anonymous--for instead hewing to a cynical "memoirist's Twelve Step program." A few journalists, most notably Deborah Caulfield Rybak of Minneapolis's Star Tribune, have openly questioned the truthfulness of some book passages, especially segments dealing with Frey undergoing brutal root-canal surgery without the aid of anesthesia and an airplane trip during which an incapacitated Frey is bleeding, has a hole in his cheek, and is wearing clothes covered with "a colorful mixture of spit, snot, urine, vomit and blood." And then there's the time in Paris (he's supposedly fled to Europe after jumping bail in Ohio) when, on his way to commit suicide by throwing himself into the Seine, Frey stops into a church to have a good cry. There, a "Priest," while pretending to listen to Frey's description of his wrecked life, makes a lunge for Frey's crotch. "You must not resist God's will, my Son," says the priest. A vicious beatdown ensues, with Frey possibly killing the grasping cleric, whom the author kicked in the balls 15 times. Mon dieu!

Frey told Cleveland's Plain Dealer in a May 2003 interview that the book was straight nonfiction, claiming that his publisher, Doubleday, "contacted the people I wrote about in the book. All the events depicted in the book checked out as factually accurate. I changed people's names. I do believe in the anonymity part of AA. The only things I changed were aspects of people that might reveal their identity. Otherwise, it's all true." However, the book, which has been printed scores of times worldwide, has never carried a disclaimer acknowledging those name changes (or any other fictionalization). Frey told us that his publisher "felt comfortable running it" without a disclaimer and that he "didn't ask or not ask" for one. "I didn't frankly even think about it."

In subsequent book store appearances (Frey can draw 1000+ fans and celebrity worshipers like Lindsay Lohan) and interviews, he has repeated the claim that "A Million Little Pieces" is truthful. And he has never shied away from discussing his criminal past.

In a recent "Meet The Writers" interview for Barnes & Noble's web site, Frey was asked about his history of incarceration. "I was in jail a bunch of times," he answered, "The last time I was in for about three months." When asked if books offered a bit of solace behind bars, Frey replied, "Yeah, I mean there's nothing to do there. You can go out to the yard and walk around or shoot hoops or lift weights. I didn't really want to do anything, so I spent most of my time reading books." Frey added that during that last three-month stretch he knocked off "Don Quixote," "War and Peace," and "The Brothers Karamazov." He also sampled some Proust, but found it too boring. "When you have literally hours and hours and hours a day to do nothing because you're locked in a cell, I found that the best way to pass time was to pick up books."

In a recent "Meet The Writers" interview for Barnes & Noble's web site, Frey was asked about his history of incarceration. "I was in jail a bunch of times," he answered, "The last time I was in for about three months." When asked if books offered a bit of solace behind bars, Frey replied, "Yeah, I mean there's nothing to do there. You can go out to the yard and walk around or shoot hoops or lift weights. I didn't really want to do anything, so I spent most of my time reading books." Frey added that during that last three-month stretch he knocked off "Don Quixote," "War and Peace," and "The Brothers Karamazov." He also sampled some Proust, but found it too boring. "When you have literally hours and hours and hours a day to do nothing because you're locked in a cell, I found that the best way to pass time was to pick up books."

In a July 2005 interview, Frey recalled reading some of those classics to a fellow inmate, an illiterate accused double murderer nicknamed Porterhouse. "We got to enjoy the books at the same time, which was cool," Frey said. The author's Ohio jailhouse interactions with Porterhouse kick off the best-selling "My Friend Leonard," (currently #9 on the Times nonfiction list, also thanks to Winfrey). The first memoir ends with Frey leaving Minnesota's Hazelden rehab clinic, and "My Friend Leonard" picks up, months later, with him on the 87th day of a three-month jail term.

In an interview with blogger Claire Zulkey, Frey compared those two stints: "Jail is really fucking boring, and occasionally, really fucking scary. It is about doing time and getting it over with and staying out of trouble. Rehab is about fixing and changing your life. It, however, can also be boring and scary."

When recalling criminal activities, looming prison sentences, and jailhouse rituals, Frey writes with a swaggering machismo and bravado that absolutely crackles. Which is truly impressive considering that, as TSG discovered, he made much of it up. The closest Frey has ever come to a jail cell was the few unshackled hours he once spent in a small Ohio police headquarters waiting for a buddy to post $733 cash bond.

![]()

Winfrey's pick of "A Million Little Pieces" was unexpected since it overflows with vulgar and graphic language. It marked her abrupt and bracing return to the selection of contemporary authors after more than three years of choosing classics (and propelling those titles, often for months at a time, to the top of bestseller lists nationwide). Prior to tabbing Frey's book, Winfrey's other 2005 book club choices were three William Faulkner novels. Winfrey had selected books by John Steinbeck, Pearl Buck, Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Leo Tolstoy, and Carson McCullers in the two prior years.

The coronation of "A Million Little Pieces" came in September, when Winfrey told a Chicago studio audience (which included Frey's mother Lynne) that she had chosen a book that she "couldn't put down...a gut-wrenching memoir that is raw and it's so real..." She would later say that, "After turning the last page...You want to meet the man who lived to tell this tale."

During the October show, which featured Frey as its only guest, Winfrey discussed details of that tale. He was, she said, "the child you pray you never have to raise," a raging, drug-abusing teenager who had been arrested 11 times by age 19. In college, he drank to excess, took meth, freebased cocaine, huffed glue and nitrous oxide, smoked PCP, ate mushrooms, and was "under investigation by police." By the time he checked into Hazelden in late-1993, Frey, then 23, was "wanted in three states," added Winfrey. Though Frey's book does not name the Minnesota clinic in which he stayed, the author has subsequently identified Hazelden as that rehab facility.

By that point, he had added three more arrests to his rap sheet (which now totaled 14 busts), including his multiple-felony bust for that melee with Ohio cops, a confrontation that started when Frey struck a foot patrolman with his car, according to the book. That episode serves as a crucial and transitional moment in "A Million Little Pieces."

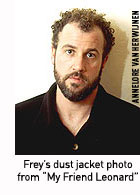

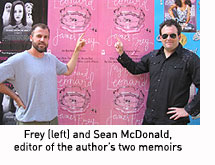

"I know that, like many of us who have read this book, I kept turning to the back of the book to remind myself, 'He's alive. He's okay," Winfrey said. In essence, that is part of the book's narrative power and a primary marketing tool. All this terrible stuff actually happened to a guy named James Frey, a former degenerate who survived drug and alcohol addiction, escaped his criminal past, and somehow avoided a relapse in the decade-plus since leaving Hazelden. When Doubleday sent the book's galleys out to reviewers, editor Sean McDonald wrote a letter touting Frey's "fearless candor," while a publicity manager hailed his "unprecedented honesty."

"I know that, like many of us who have read this book, I kept turning to the back of the book to remind myself, 'He's alive. He's okay," Winfrey said. In essence, that is part of the book's narrative power and a primary marketing tool. All this terrible stuff actually happened to a guy named James Frey, a former degenerate who survived drug and alcohol addiction, escaped his criminal past, and somehow avoided a relapse in the decade-plus since leaving Hazelden. When Doubleday sent the book's galleys out to reviewers, editor Sean McDonald wrote a letter touting Frey's "fearless candor," while a publicity manager hailed his "unprecedented honesty."

Of course, if "A Million Little Pieces" was fictional, just some overheated stories of woe, heartache, and debauchery cooked up by a wannabe author, it probably would not get published. As it was, Frey's original manuscript was rejected by 17 publishers before being accepted by industry titan Nan Talese, who runs a respected boutique imprint at Doubleday (Talese reportedly paid Frey a $50,000 advance). According to a February 2003 New York Observer story by Joe Hagan, Frey originally tried to sell the book as a fictional work, but the Talese imprint "declined to publish it as such." A retooled manuscript, presumably with all the fake stuff excised, was published in April 2003 amid a major publicity campaign.

Frey told Winfrey that he wrote "A Million Little Pieces" with the assistance of "like 400 pages" of very detailed Hazelden records, documents that he told her included "legal records." In a promotional CD prepared by Doubleday, Frey reported gathering "all of my records: medical, psychological, financial, criminal, and otherwise" that were kept during his treatment center stay. Declining a TSG request to examine those documents, Frey said, "Once I start providing records for people it never ends for me...I feel like I provided the records to the people who were appropriate, who needed to see them." He added that he turned down The New York Times when the newspaper sought to review the material, though he showed Hazelden records to Winfrey staff members.

Comments (12)